TBA21 Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary

About

Exhibitions

TBA21–Academy

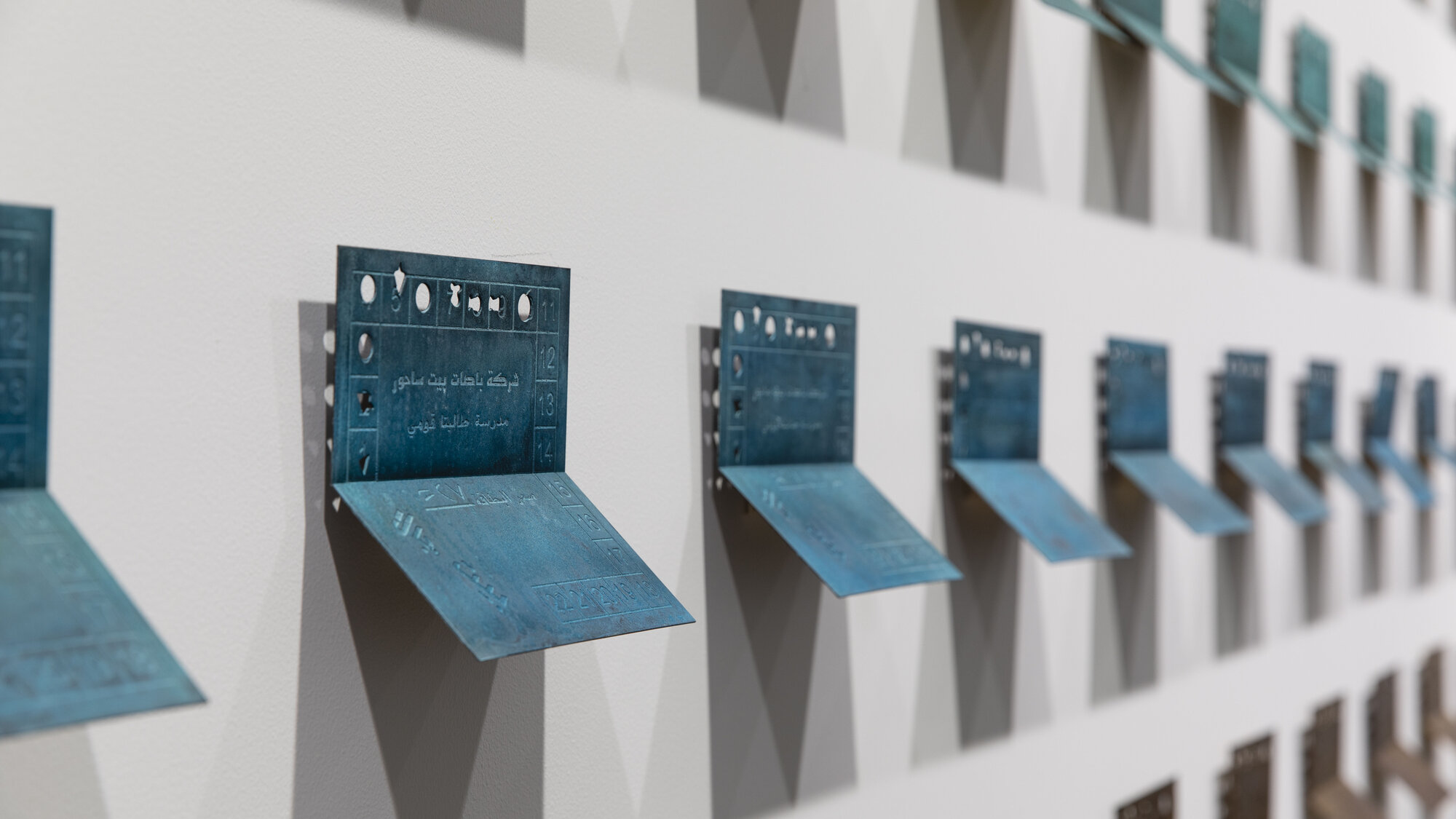

Collection

Program

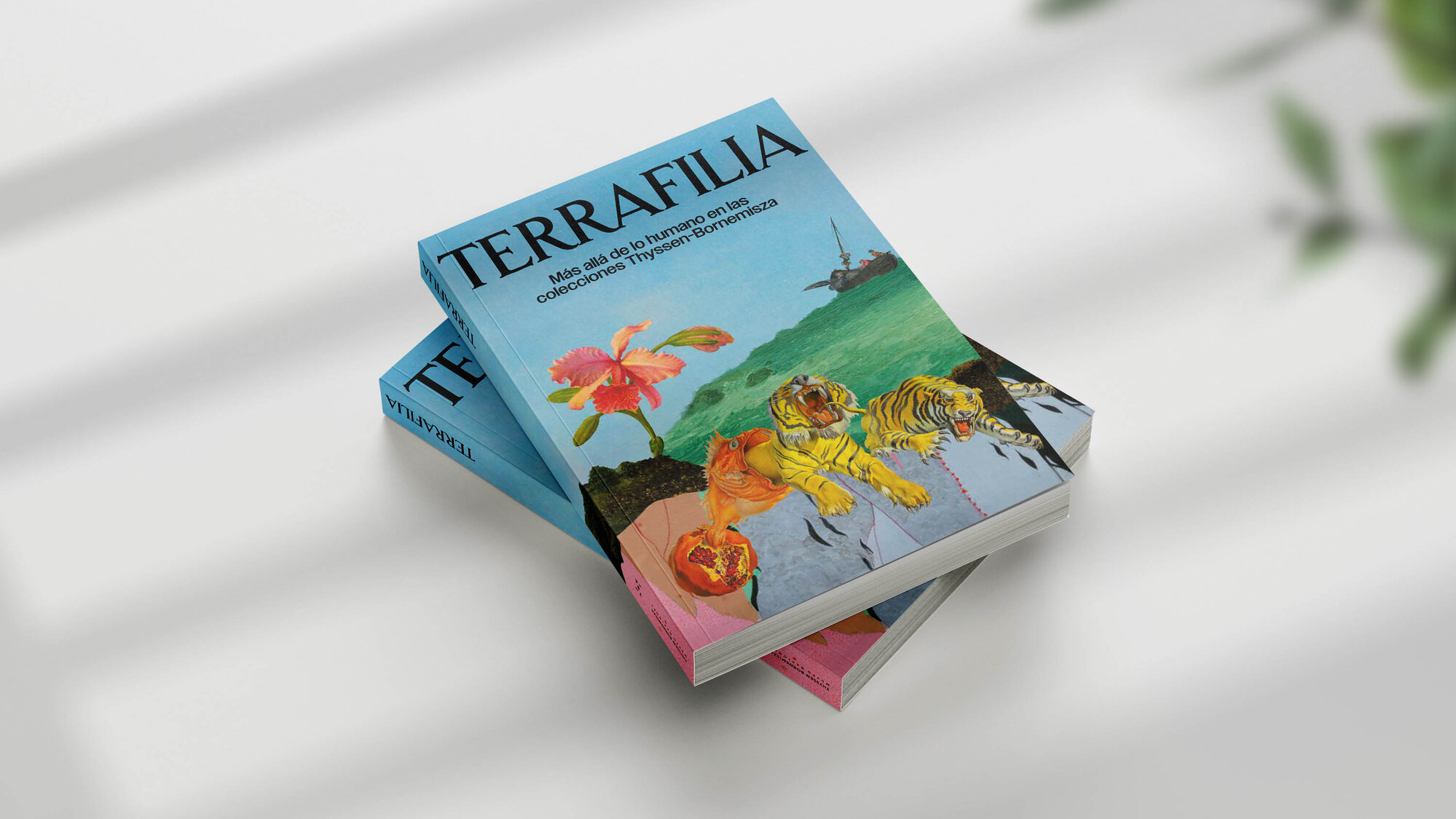

Publications

Archive

TBA21 Sites - physical and digital

MNTB Madrid

Ocean Space Venice

C3A Córdoba

AHF Jamaica

Ocean-Archive.org

TBA21 on st_age