Plata

Vegetal Acupuncture: Plants for a Future without Petroleum, 2022

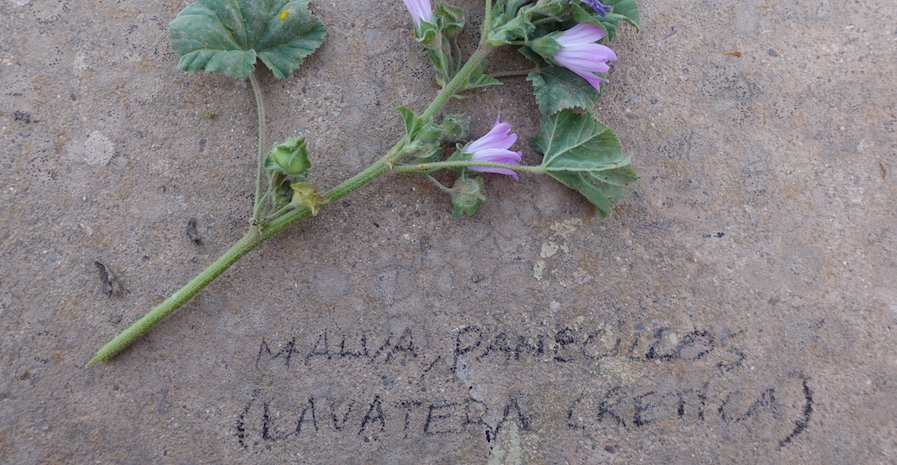

Plata/Semilla Silvestres, documentation, research process, 2022

Plata/Semilla Silvestres, documentation, research process, 2022

Plata/Semilla Silvestres, documentation, research process, 2022

Vegetal Acupuncture: Plants for a Future without Petroleum, commissioned by TBA21 Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary for Abundant Futures, is a multi-year project conducted by Plata with Semillas Silvestres, is an eco-poetic intervention aimed at reversing the depletion of plant coverage in cities and reconciling the needs of vegetal ecosystems with the cultural understanding of humans. It focuses on plants for a petrol-free future, identified for their uses as petroleum substitutes, which have been planted across otherwise disused spaces of the C3A.

By injecting biodiversity to spaces considered hostile to cultivation, Plata and Semillas Silvestres, a research center focused on seed production, instigate an urgent discussion of substitution and collaboration with plants in light of the imminent energy transition.

--

Fossl fuels, natural dyes and textiles

Dyer’s rocket (Reseda luteola), rose madder (Rubia tinctorum), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), woad (Isatis tinctoria), camelina (Camelina sativa), rapeseed (Brassica napus), sunflower (Helianthus annuus) and soybean (Glycine max), flax/linseed (Linum usitatissimum), hemp (industrial C. sativa), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), common nettle (Urtica dioica),

Fossil fuels are organic deposits derived from plant and animal organisms incorrectly referred to as “minerals.” Large quantities of the energy sources on Earth were once concentrated in plants, making bio-substitutes amply available. Oleaginous species like camelina (Camelina sativa) can be used as biodiesel, similar to rapeseed oil (Brassica napus), sunflower oil (Helianthus annuus), and soybean (Glycine max).

The majority of natural dyes are of vegetal origin and a wide range of colors and hues can be obtained from roots, fruits, bark, or leaves. They are first boiled to extract the dye components, and then the clothes are submerged into the colored water. Red dyes like Turkey red can be extracted from the roots of the rose madder (Rubia tinctorum). Dyer’s rocket (Reseda luteola) contains a flavonoid that produces a bright yellow dye, suitable for wool, linen, and even silk, especially when harvested just before it bears fruit. When combined with the indigo from woad (Isatis tinctoria) it produces green hues.

The fact that a wealth of products that were once made from plants are now produced from petroleum derivatives points to the richness of available petroleum-free alternatives. This is also the case of textiles: raw fibers from hemp (industrial C. sativa variety), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), linseed (Linum usitatissimum), and common nettle (Urtica dioica) are used for ropes, fabrics, and clothing. The richness of plant materials is all around us, always helping to provide for more sustainable, local, and renewable choices.

--

Wood, basketry, mats and tools

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), thornless blackberry (Rubus ulmifolius), Spanish broom (Spartium junceum), Esparto (Stipa tenacissima), Bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria), sponge gourd (Luffa aegyptiaca), rye (Secale cereale)

Plants, writes philosopher Emanuele Coccia, have long been perceived as “the cosmic ornament, the inessential and multicolored accident that reigns in the margins of the cognitive field.” Viewed as urban decoration or weeds, plants in cities are designated either for contemplation or elimination.

Before the invention and industrial application of plastic, wood was one of the materials most frequently used in the creation of endless variations of practical and decorative items. This courtyard is dedicated to boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), a very dense and heavy wood used throughout for centuries as a substitute for ivory. Today it is still employed to fabricate all kinds of musical instruments and furniture, as well as for in wood engravings. Basket weaving is one of the most diverse and ancient plant-based crafts.

Baskets have been used for the transportation and storage of goods since the Neolithic period. Their production depends on environmental and vegetal resources, economic interactions and trade routes, social aspects of labor, and community and sustainable management. Many plants with flexible leaves and stems that can be used for this purpose, including woody plants like the ones planted in this courtyard: the thornless blackberry (Rubus ulmifolius) and the Spanish broom (Spartium junceum). The stems of the Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) have been used for baskets, ropes, and brooms.

Mats and carpets are fabricated from vegetal fibers, such as the Esparto (Stipa tenacissima), a vulnerable perennial grass originally from esteparian habitats. The esparto leaves are slim and long, reaching up to one meter height. The southeastern area of the Iberian Peninsula and the Maghreb plateaus are some of the most productive regions of esparto. This grass is harvested in summer, dried in the sun, then submerged in rafts to ferment, and dried again. The result is unique and highly recognizable leaves which, since ancient times, have been curled and braided in different shapes and techniques, to create an endless variety of carpets, ornaments, shoes, and baskets.

Taking advantage of their shape, gourds, calabashes, and pumpkins have traditionally been used as containers, bottles, and vessels. In Spain, the bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria)— also known as calabaza del pelegrín or botía de pastor —was originally used as an efficient and ecological tool for shepherds and travelers to store liquids. Through the centuries, this pumpkin has turned into a symbol of the Camino de Santiago, transported by pilgrims to quench their thirst. Another example is the sponge gourd, shaped like a cucumber, which is only edible when it is immature. When it ripens, it becomes too fibrous and it is mainlyused as a bath sponge.

By injecting biodiversity to spaces considered hostile to cultivation, Plata and Semillas Silvestres, a research center focused on seed production, instigate an urgent discussion of substitution and collaboration with plants in light of the imminent energy transition.

--

Fossl fuels, natural dyes and textiles

Dyer’s rocket (Reseda luteola), rose madder (Rubia tinctorum), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), woad (Isatis tinctoria), camelina (Camelina sativa), rapeseed (Brassica napus), sunflower (Helianthus annuus) and soybean (Glycine max), flax/linseed (Linum usitatissimum), hemp (industrial C. sativa), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), common nettle (Urtica dioica),

Fossil fuels are organic deposits derived from plant and animal organisms incorrectly referred to as “minerals.” Large quantities of the energy sources on Earth were once concentrated in plants, making bio-substitutes amply available. Oleaginous species like camelina (Camelina sativa) can be used as biodiesel, similar to rapeseed oil (Brassica napus), sunflower oil (Helianthus annuus), and soybean (Glycine max).

The majority of natural dyes are of vegetal origin and a wide range of colors and hues can be obtained from roots, fruits, bark, or leaves. They are first boiled to extract the dye components, and then the clothes are submerged into the colored water. Red dyes like Turkey red can be extracted from the roots of the rose madder (Rubia tinctorum). Dyer’s rocket (Reseda luteola) contains a flavonoid that produces a bright yellow dye, suitable for wool, linen, and even silk, especially when harvested just before it bears fruit. When combined with the indigo from woad (Isatis tinctoria) it produces green hues.

The fact that a wealth of products that were once made from plants are now produced from petroleum derivatives points to the richness of available petroleum-free alternatives. This is also the case of textiles: raw fibers from hemp (industrial C. sativa variety), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), linseed (Linum usitatissimum), and common nettle (Urtica dioica) are used for ropes, fabrics, and clothing. The richness of plant materials is all around us, always helping to provide for more sustainable, local, and renewable choices.

--

Wood, basketry, mats and tools

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), thornless blackberry (Rubus ulmifolius), Spanish broom (Spartium junceum), Esparto (Stipa tenacissima), Bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria), sponge gourd (Luffa aegyptiaca), rye (Secale cereale)

Plants, writes philosopher Emanuele Coccia, have long been perceived as “the cosmic ornament, the inessential and multicolored accident that reigns in the margins of the cognitive field.” Viewed as urban decoration or weeds, plants in cities are designated either for contemplation or elimination.

Before the invention and industrial application of plastic, wood was one of the materials most frequently used in the creation of endless variations of practical and decorative items. This courtyard is dedicated to boxwood (Buxus sempervirens), a very dense and heavy wood used throughout for centuries as a substitute for ivory. Today it is still employed to fabricate all kinds of musical instruments and furniture, as well as for in wood engravings. Basket weaving is one of the most diverse and ancient plant-based crafts.

Baskets have been used for the transportation and storage of goods since the Neolithic period. Their production depends on environmental and vegetal resources, economic interactions and trade routes, social aspects of labor, and community and sustainable management. Many plants with flexible leaves and stems that can be used for this purpose, including woody plants like the ones planted in this courtyard: the thornless blackberry (Rubus ulmifolius) and the Spanish broom (Spartium junceum). The stems of the Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) have been used for baskets, ropes, and brooms.

Mats and carpets are fabricated from vegetal fibers, such as the Esparto (Stipa tenacissima), a vulnerable perennial grass originally from esteparian habitats. The esparto leaves are slim and long, reaching up to one meter height. The southeastern area of the Iberian Peninsula and the Maghreb plateaus are some of the most productive regions of esparto. This grass is harvested in summer, dried in the sun, then submerged in rafts to ferment, and dried again. The result is unique and highly recognizable leaves which, since ancient times, have been curled and braided in different shapes and techniques, to create an endless variety of carpets, ornaments, shoes, and baskets.

Taking advantage of their shape, gourds, calabashes, and pumpkins have traditionally been used as containers, bottles, and vessels. In Spain, the bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria)— also known as calabaza del pelegrín or botía de pastor —was originally used as an efficient and ecological tool for shepherds and travelers to store liquids. Through the centuries, this pumpkin has turned into a symbol of the Camino de Santiago, transported by pilgrims to quench their thirst. Another example is the sponge gourd, shaped like a cucumber, which is only edible when it is immature. When it ripens, it becomes too fibrous and it is mainlyused as a bath sponge.

FIND MORE

Basketry and Beyond. Weaving techniques

Christina Nunes, "Biofuel explained", in National Geographic, July 15, 2019.

Madeleine Muzdakis, “Basket Weaving and How You Can Make Your Own”, in My Modern Met, November 1, 2020.

Chalmin-Pui, L.S., Roe, J., Griffiths, A., Smyth, N., Heaton, T., Clayden, A., & Cameron, R., “It made me feel brighter in myself”. The health and well-being impacts of a residential front garden horticultural intervention”, in Landscape and Urban Planning 205 (2021): 103958.

Ekwealor, K. U., Echereme, C. B., Ofobeze, T. N., & Okereke, C. N., “Economic

Importance of Weeds: A Review”, in Asian Plant Research Journal 3 (2019), 1-11.

Maria Julia Martínez García, “Plantas tintóreas, la naturaleza y el color en el arte de teñir”, in Espores, May 22, 2018.

Arora, J., Agarwal, P. and Gupta, G., “Rainbow of Natu- ral Dyes on Textiles Using Plants Extracts: Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Processes”, in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 7 (2017): 35-47.

Janick, Jules et al., “The cucurbits of mediterranean antiquity: identification of taxa from ancient images and descriptions.", in Annals of botany vol. 100,7 (2007): 1441-57.

Christina Nunes, "Biofuel explained", in National Geographic, July 15, 2019.

Madeleine Muzdakis, “Basket Weaving and How You Can Make Your Own”, in My Modern Met, November 1, 2020.

Chalmin-Pui, L.S., Roe, J., Griffiths, A., Smyth, N., Heaton, T., Clayden, A., & Cameron, R., “It made me feel brighter in myself”. The health and well-being impacts of a residential front garden horticultural intervention”, in Landscape and Urban Planning 205 (2021): 103958.

Ekwealor, K. U., Echereme, C. B., Ofobeze, T. N., & Okereke, C. N., “Economic

Importance of Weeds: A Review”, in Asian Plant Research Journal 3 (2019), 1-11.

Maria Julia Martínez García, “Plantas tintóreas, la naturaleza y el color en el arte de teñir”, in Espores, May 22, 2018.

Arora, J., Agarwal, P. and Gupta, G., “Rainbow of Natu- ral Dyes on Textiles Using Plants Extracts: Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Processes”, in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 7 (2017): 35-47.

Janick, Jules et al., “The cucurbits of mediterranean antiquity: identification of taxa from ancient images and descriptions.", in Annals of botany vol. 100,7 (2007): 1441-57.

Pipilotti Rist

Related Legs (Yokohama Dandelions), 2001

Installation view: Passages. Travels in Hyperspace. Works from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection, LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial, Gijón, Spain, 2010 | Photo: Marcos Morilla

Related Legs (Yokohama Dandelions), 2001

Installation view: Passages. Travels in Hyperspace. Works from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection, LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial, Gijón, Spain, 2010 | Photo: Marcos Morilla

Plata is an artistic collective project by Jesús Alcaide, Gaby Mangeri, and Javi Orcaray. It was

founded in Córdoba, Spain, in 2021.

Semillas Silvestres was founded in Córdoba, Spain, in 1992.

founded in Córdoba, Spain, in 2021.

Semillas Silvestres was founded in Córdoba, Spain, in 1992.